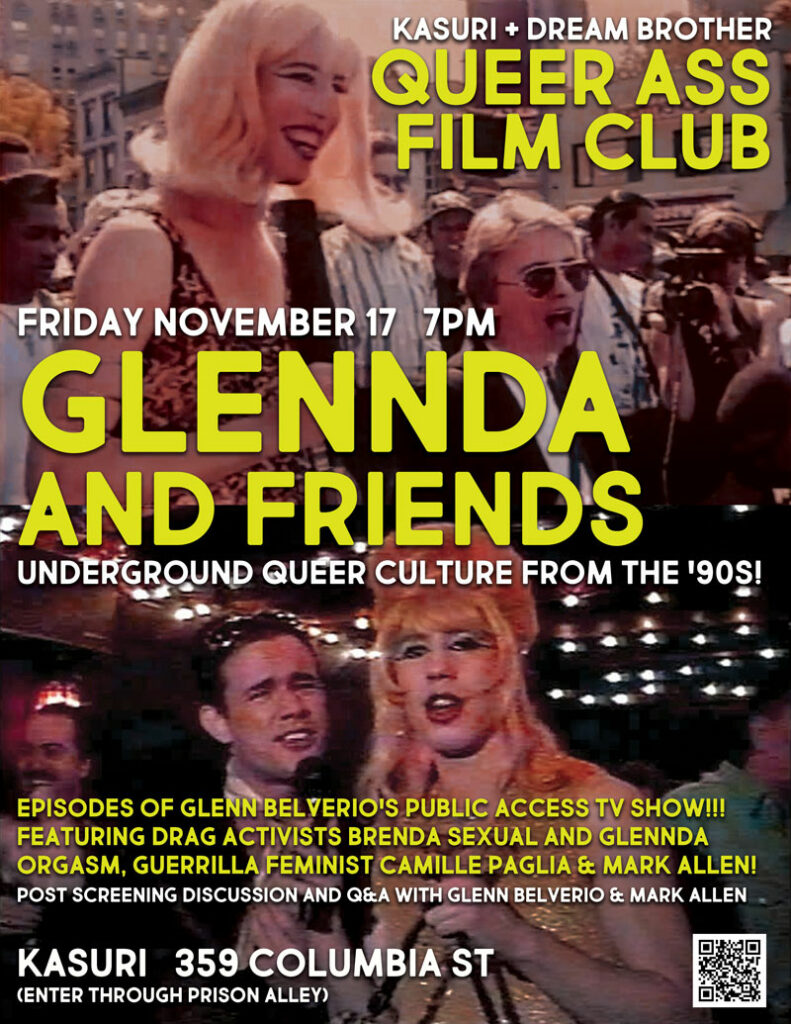

Sponsored by Kasuri and Dream Brother

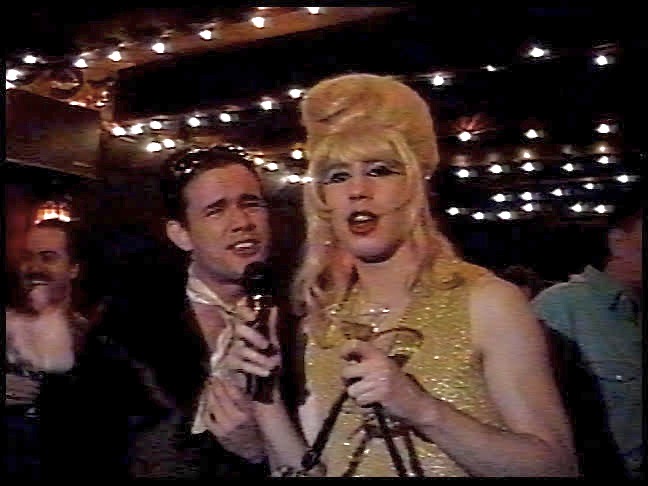

Kasuri and Dream Brother sponsored an evening of “The Brenda and Glennda Show” and “Glennda and Friends”, starring Glenn Belverio and Hudson resident Mark Allen.

The show aired on Manhattan Cable’s public access channel in the early to mid-90s. I decided to ask the duo a few more questions about their experiences and alternative media.

Q: We now live in a world where anyone can have a youtube or instagram channel. Do you think that public access served a similar purpose pre-internet?

Glenn Belverio: It was definitely similar, but not quite as easy. With Public Access, you had to have the means to produce a show and it needed to be on broadcast-format tape, which in those days was ¾” tape aka U-Matic. And there were rules you had to follow for the tape, like time code and a countdown at the beginning, and the show needed to clock in at 29 minutes. And there were costs involved. You needed a camera and camera people and a means to edit the show. If you wanted a professional look, you had to find a studio to shoot in. I suppose some people slapped their shows together with two VCRs instead of hiring an editor, which was cool in its own way, very DIY, very “I need to get my message out by any means possible.”

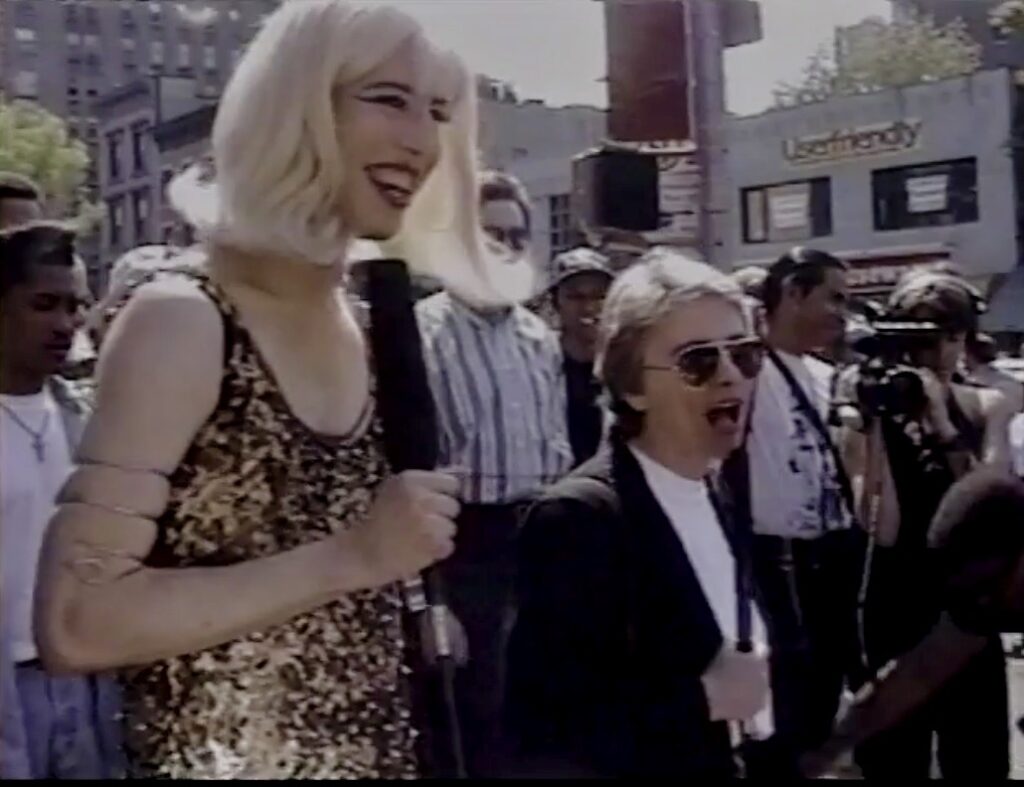

For The Brenda and Glennda Show and Glennda and Friends I was fortunate enough to have a professional co-producer, Stevin Azo Michels, who worked and still works at NYU. He is a skilled video editor and proficient videographer. (Witness the way Stevin, and our other cameraperson Julie Clark, filmed the hectic street confrontation between Glennda and Camille Paglia and the anti-porn demonstrators in Glennda and Camille Do Downtown, a 1993 episode of Glennda and Friends.) So, our production values were much higher than the average Public Access program.

There were also some politics involved in getting a time slot on Manhattan Public Access. Your show needed to be reviewed before being accepted—however, I don’t remember the criteria as being particularly strict. They basically reviewed it to make sure you weren’t breaking the standard rules: no hardcore pornography (although you could have that on Leased Access) and no extreme violence. Light porn was fine though, since we did have some of that on our show. And then you had to negotiate a time slot with the station manager. I seemed to remember you’d get a good one if the programmer really liked you and/or your show, or you were very professional and polite when you met with them. You had to woo them a little bit if you didn’t want to be relegated to the 5am time slot. (Although the 3am time slot was actually as good as prime time in downtown NYC: During that time, you had a captive audience of coke heads and drunks who were coming home from the bars and clubs and they would tune into your show because there was nothing else to do. Our show had two weekly time slots: 8:30pm and 3am.)

Overall, Public Access was a very democratic forum, and was a radical alternative to mainstream television, which was especially terrible in the ‘90s. Public Access provided a platform for just about anyone who wanted to be on TV, from the guy who did his show from his bathtub, to left-wing activists like Paper Tiger to club kids, vinyl fanatics, Mrs. Mouth and various downtown artists and freaks.

Mark Allen: Cable access television in the 90s reminds me of the internet in the early 00s. It was very difficult to have a web presence in 2000. You had to learn html, you had to finagle expensive server space, you had to learn to code. It required a lot of elbow grease. Your only way of getting attention was to be legitimately interesting, and hope that word of mouth and email spread your web presence far and wide. There were fewer rules. It was like the Wild West. Cable access television (especially in a place like NYC) in the 90s was similar to this. Having a show required real work and commitment, there were no ratings or likes, so you could just do whatever you wanted. Stars of cable access in NYC in the 90s rose to popularity based only on talent and content. There was no algorithm.

It was exciting to be a part of Glenn Belverio’s show at the time. His show was wild and funny, but there were clearly smarts behind it. He dealt with subjects no one else would touch or even knew about, captivating audiences who loved him or hated him but couldn’t look away.

Q: Would you say that public access and some press, such as the Village Voice, served a purpose as an alternative media source? Did it help bring under-represented communities together?

Glenn Belverio: Absolutely. The only way to get news about gay people and the AIDS crisis was from the Village Voice and a handful of gay magazines, plus Public Access news shows like Out in the ‘80s and Out in the ‘90s. Because the mainstream media was definitely not reporting on this stuff, except in a negative way and in small bites of information. Queer people, artists and activists used Public Access to get the word out.

The reason that Brenda Sexual (Duncan Elliott) and I conceived The Brenda and Glennda Show in 1990 is because we were frustrated by gay people who were either in the closet and/or did not want to get involved in AIDS activism. We knew that people who were channel surfing would most likely stop at a channel when they saw a drag queen—because queens are entertaining, funny and seemingly non-threatening. So, we used drag as a Trojan horse to get the word out about Queer visibility, anti-gay violence, homophobia and the AIDS crisis.

Mark Allen: I can only speak as a New Yorker from 1990 on, the year I moved to NYC. Back then The Village Voice was essential in a sense, but even when it was good it had an aura of “old.” What I most remember was the fanzine explosion in the early 90s. To me that was an alternative media source that brought under-represented communities together in an exciting way. There were so many of them! NYC was different because we had many outlets for underground press and fanzines, like Kim’s and SeeHear. But over time (thanks to the hard work of their DIY creators) fanzines began to creep into the “alternative” newsstand sections of major bookstores like Borders, nationwide.

Q: Is there an alternative media today, or is everything (youtube, IG, etc) “alternative” media? Is there a mainstream media?

Glenn Belverio: The Brooklyn Museum has a new exhibition up called Copy Machine Manifestos: Artists Who Make Zines and three issues of the zine I made in the early ‘90s with Emily Nahmanson, Pussy Grazer, are featured in it. (Along with a 1993 Glennda and Friends episode The Post-Queer Tour co-starring zine queen Bruce LaBruce.) Back in the ‘70s, ‘80s and ‘90s, zines were a form of alternative media and now I’m hearing from my Gen Z network that young people are once again producing their own zines. (My friend the London-based artist and veteran zine creator Rachael House teaches zine workshops for young people.) The reason some young people are getting into this is because they are fed up with the instant gratification and ephemeral nature of TikTok, IG etc. They want to get into something that frees people from the slavery of screens. And to create something that is tangible and feels special—not something to read in three seconds and scroll past.

There is still a mainstream media—network news, CNN—but in today’s world, it’s competing in real time with a second screen. Many people are scrolling through social media while they’re watching the news. People are processing fragments of newsbites while looking at specious memes or jokey reels or images of their favorite muscle studs on IG. And then there are people that don’t watch or read the mainstream news at all. The only news they get is what their friends ate while on holiday.

Mark Allen: The lines separating the two have been scrambled, over and over. Honestly, at my age I’ll confess I find the new media landscape overwhelming and complex. I participate in it with enthusiasm, but am haunted feeling there’s something younger people are seeing in it that is invisible to me. Imagine what it will look like in another fifty years.

Q: Where do you look for “alternative” media? Do you see your lives represented now as opposed to twenty-thirty years ago? How has social media helped/hurt upcoming generations of LGBT youth?

Glenn Belverio: I guess I don’t really look for alternative media. Podcasts are probably the best example of alternative media, and while I’ve been interviewed on a few, I don’t particularly enjoy listening to them. I’d rather read a good non-fiction book, like Tarantino’s Cinema Speculation or Thurston Moore’s memoir Sonic Life.

I’m now 57 and I don’t need my life represented by the media. I think only younger people need that, because they’re still trying to figure out who they are. Brenda Sexual and Glennda Orgasm were trailblazers in queer representation on TV in the ‘90s. In her new, meticulously researched book Glitter and Concrete: A Cultural History of Drag in New York City, author and journalist Elyssa Maxx Goodman discusses the drag legacy of The Brenda and Glennda Show, in her chapter on the 1990s:

‘Brenda and Glennda brought drag to the daylight, to the streets, with episodes filmed on the Circle Line, at the Empire State Building, and even the Trump Taj Mahal in Atlantic City, where they’d speak to people on camera in the hopes of creating “Gay, Lesbian, and Drag Queen Visibility.” This was a time when, aside from Wigstock, there was rarely a drag queen seen outside of nightlife, let alone on television, let alone during the day, let alone talking to people who had maybe never seen a drag performer.’

Regarding young LGBTQ+ on social media, what I’ve seen is this disturbing trend of Maoist Red Guard groupthink—a mob mentality where humorless queers engage in scold culture and go after anyone who isn’t toeing the party line that’s trickled down to them from queer theorists like Judith Butler.

But that’s just one part of it. I imagine that a lot of young queer people use social media to feel less isolated, especially if they live outside of urban centers. When I was young and living on a farm in the middle of the woods in New Jersey, the only way to connect with other gay people or other like-minded people was by starting a mail correspondence through ads in a newspaper called the Aquarian Arts Weekly, which was basically the NJ/Philly-area version of The Village Voice. This was pre-email, so you were basically corresponding with people via the Pony Express. And then maybe there were opportunities to meet the people you were corresponding with, which involved driving for at least an hour. Not just for dates or sexual encounters. For me, it was also meeting people who were into the same music I was into, so I also corresponded with a lot of women. It was with some of these women that I made my first trip to the Pyramid Club on Ave A, back in 1985. Today it’s much easier for young gays to connect, for romance and friendships, because of the immediacy of social media. And then of course there are hookup apps, which I didn’t have probably until I was in my late 30s and early 40s. Remember AOL chat rooms? And phone sex lines where you couldn’t even see the person? You were basically just blindly throwing your keys down to the street.

Mark Allen: Within the capacity queer representation, I would say again that things are largely more complex. But I think that’s in a large part because what it means to be “queer” has widened and become more complex. The whole expanding alphabet communities, labels, tribes, etc. This combined with a more compounded media landscape, I don’t know. There’s a constant firehose of media stimulation now. There’s less time to think. I don’t need to look for representation because it’s all around me. Things feel less special. The private obsession is gone.

Q: Has “alternative media” maybe gone too far today with unverified sources of information?

Glenn Belverio: Much ado has been made about misleading or fake news content on social media, such as specious or completely false memes that lazy thinkers re-post without fact-checking. Even smart people we know who should know better.

There’s also false and manipulative content flooded into our social media channels by foreign governments and I’m not just talking about the so-called election interference by Russia. The Chinese Communist Party generates a lot of propagandistic content designed to deceive U.S. audiences. Remember how outraged and disgusted liberals were when they saw that out-of-context video of the Dalai Lama asking a young boy to suck his tongue? The same liberals who would lie down and stop traffic to “Free Tibet.” Why was this “news” item suddenly dominating our social channels? It’s because the CCP wants to defame and discredit the Dalai Lama among American liberals so they can overexert their hand in choosing his successor. These stories don’t just drop into the news cycle randomly. But people react to them without questioning, Where did this come from? Who created this content?

Mark Allen: We live in a post-truth world. We watch with resignation as political and cultural figures turn lies and misdeeds into perceived triumphs by spinning the wheels of ever-expanding multimedia around them, sometimes they do it without lifting a finger, their audience or “tribe” does it for them. Sometimes the multimedia does it by itself almost robotically, which is creepy. Amongst all the static it’s easier for businesses and corporations to rip people off. It’s all right out in the open. It all feels very black-is-white, up-is-down. I think there’s a sense of hopelessness because we rely on the technology that feeds this complex media, like it’s our lifeblood. This is a dark component of current media I don’t like, and find frightening. Is there an alternative media now? If there is, I would say it ate itself by its own design and now is part of a much larger beast that hasn’t been labeled or identified, or even seen. It’s best not to think about it too much. Distracting ourselves reassures us. A billion witless people with social media accounts is far more dangerous to humanity than sentient A.I. could ever be.

Regarding Lady Bunny:

Glenn Belverio: The Lady Bunny I love is the one who is constantly touring and putting on un-PC, raunchy, hilarious and brilliant performances. She has filled the void left behind by the passing of Joan Rivers. Last February, I was in Miami for a Glennda screening at the Faena Hotel and my friend Ben and I were invited to Bunny’s pool party at the hotel where Wigwood was taking place—a sort of small version of Wigstock. Bunny did a side-splitting parody of Wet-Ass Pussy called Dry-Ass Pussy, complete with a homemade costume that was meant to make her look like a skinny bikini-clad chick. Bunny is one of the most brilliant satirists of our time.

But her long and shrill political screeds on IG, which do sometimes include useful information, are either just preaching to the choir or angering those who don’t agree. So, there are no meaningful debates in the comments section, just drive-by quips like “I agree!!!!” or “Bunny, I think your wig is on too tight!”. It all seems like such a colossal waste of time as I seriously doubt that anyone’s opinion has been changed by a political rant on social media. And in general, I’m also just amazed that people have all this free time to sit on social media and post looooong political rants and engage in petty back-and-forth arguments.

I would rather see Bunny channel that energy into her performance pieces, which are her forte. The dirtbag Left/Bernie Bro routine has become tedious. And I’m saying this as someone who was a Bernie Sanders supporter and voted for him in the primaries.

Mark Allen: I just noticed the Lady Bunny question. I haven’t thought of her in years. Remember that time at Limelight she got booed off stage for performing in blackface? But it turned out it was only mold?