When I met Hudson-based artist Michael Lindsay-Hogg at Hudson Hall earlier this week, it was during the installation of Talking Pictures – a new solo exhibition of more than eighty original works by the man Wes Anderson calls “the Buñuel of portrait-painters.”

A menagerie of whimsical, strange faces stared at us from varying angles; it felt like we were standing in a Brechtian parlor, or some kind of wayward living room. Looking about the space, Lindsay-Hogg remarked on how glad he was that his work was being shown at Hudson Hall.

“It’s a brilliant insight to have it here,” he said, citing the organization’s centering of community. But he appreciates the space for more practical reasons, too: “I like how big the walls are.”

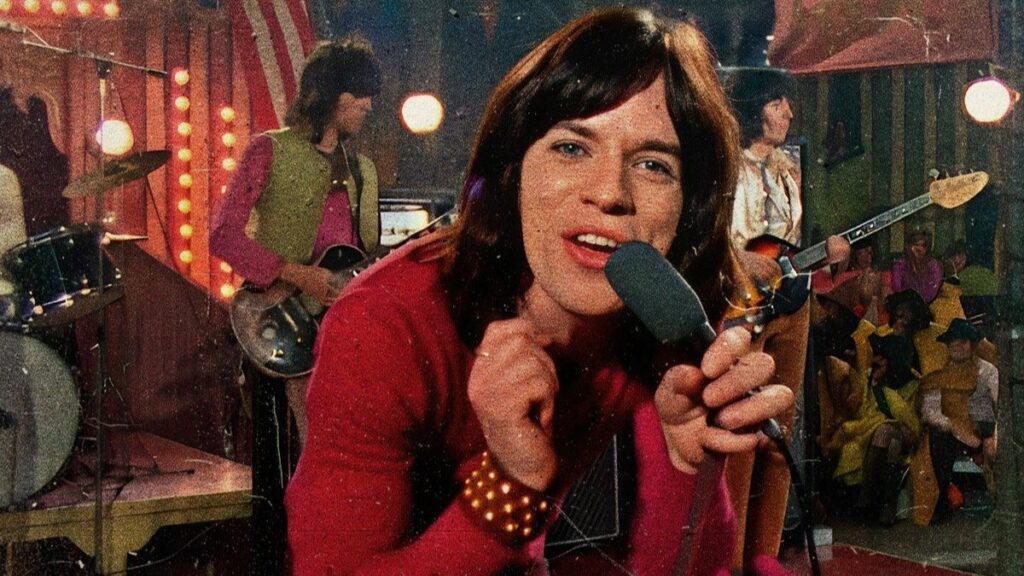

Lindsay-Hogg is most widely known for his work as a filmmaker – specifically, the prototypical music videos he made with bands like The Rolling Stones and The Who in the mid-1960s, as well as his legendary and, until recently, inaccessible documentary Let It Be (1970), which chronicles The Beatles’ production and iconic rooftop performance of their penultimate album.

It was only in recent decades that Lindsay-Hogg became a self-taught painter. His wife, Lisa Ticknor, asked him if he’d ever thought about painting. He was reluctant at first, but after Ticknor supplied him with paints and brushes, he went to work.

“The first one was okay,” he remembers. “Because I don’t have training, I’ll start a picture – and it could be a man in a suit, but it won’t be coming out that way, so I’ll turn it into a woman in a dress.”

It’s in keeping with Lindsay-Hogg’s instincts as a documentarian that these creative pivots seem to speak to him: “I quite like the mistake. The mistake points you in another direction.”

Though the paintings are recent, Lindsay-Hogg has been drawing ever since he was a little boy. “I couldn’t read until I was almost nine,” he says. “So my literature was comic books. I began to learn from them what a story was – by seeing the different panels.”

He recalls the “wonderfully odd characters” of comics like Dick Tracy and Blondie, and one can find their oddness echoed in Lindsay-Hogg’s own work. “They’re all connected in some way,” he says, gazing at his subjects. “But how are they connected?”

All of Lindsay-Hogg’s paintings are derived from his own imagination, and thus can be read as entirely fanciful. But it’s hard to look at the colorful figures in his paintings and not think of the many colorful people he’s worked with over the years. Is it possible, I ask, that you might be channeling particular scenes or individuals you’ve encountered along the way?

“If you take your brain or my brain,” he says, “it’s like a closet. And then, when you open the door, everything tumbles out. You know – there’s the top hat, the old boots, the photographs from twenty years ago, the ham sandwich you wish you’d finished. All these things coming at you. And they never go away.”

I also point out that, as a filmmaker, Lindsay-Hogg has favored stories that focus on fraternal friction – from the breakup of rock n’ rollers to TV productions of Brideshead Revisited (1981) and Master Harold… and the Boys (‘85), to the original Off-Broadway staging of Larry Kramer’s The Normal Heart. Is there a reason why he’s drawn to scenes that position small groups of people against one another, yet together?

Lindsay-Hogg thinks for a moment. “I’ve always been interested in the dynamics of people,” he says. “Whether they’re united by blood or affection. Or lack of affection.”

He adds that this is a big reason why he first started working in the theater; he enjoyed the comradeship, the team-like collaborations of actors and technicians. “You’re making a family. Your rapport and disagreements while working together have all the elements of a family.

“I miss the group,” he confesses. “Though I wouldn’t want the group around while I’m painting. I guess the group lives in my head now.”

From what can be seen on Hudson Hall’s gallery walls, the group that lives in Michael Lindsay-Hogg’s head is well-worth one’s acquaintance. “I hope people like it,” he says, displaying a respectable humility. But then, towards the end of our conversation, he also offered me a final tribute to his work that I will gladly use to conclude this essay:

“You’re going to say, ‘This is the most wonderful art show that I’ve been to. And I hope you all come.’”

The opening reception for Talking Pictures is Saturday, April 20 from 5-7pm. Michael Lindsay-Hogg will be present for the opening, and he will be leading a discussion of his documentary The Rolling Stones Rock and Roll Circus on Saturday, May 4 at 7pm.

Hudson Hall is open Tuesday through Friday, 9am to 5pm, and Saturday and Sunday from noon to 5pm. To learn more about these and other events, visit hudsonhall.org.

Ben Rendich is a filmmaker and writer. He’s in pre-production on his first feature, Sweet Confusion, and has a blog where he writes movie reviews and essays called Reflections on a Silver Screen. He lives in Catskill.